Hey

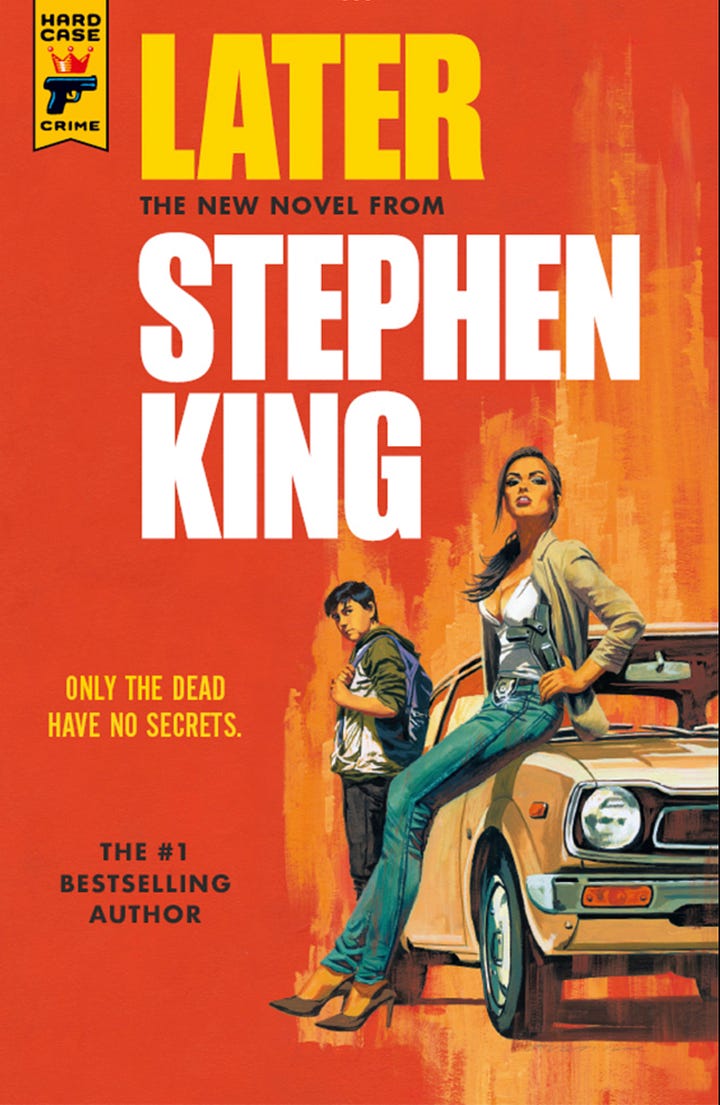

I’m reading my second Stephen King book this year—you know I love me some King. This one is called Later, and it’s a story about a boy who sees dead people, but not in a fun way: the ghosts he sees tend to hang around for a while after their death, and gradually fade away over the next couple weeks. That description struck me as a beautiful representation of presence. I don't believe in ghosts myself, but I like the idea of people having such presence, that you feel them even when they’re gone. That’s something we can all relate to, right?

My labelling job

My essay this week was an argument for labelling people, and it seemed to really resonate with folks—I got several comments both on the webpage and on other channels. If you enjoyed it, please go ahead and share it. And if you haven’t seen it yet, here you go:

It’s my job to label people.

That’s not how I like to think about it, but that’s how patients sometimes see the diagnoses doctors give them: like we’ve slapped a sticker on them that says, “Dangerous! Don’t touch!” And I get that. There’s been great progress in the public perception of mental illness, but there’s still a lot of negativity compared to physical health problems. Depression still gets taken less seriously than diabetes. And it’s worse with a diagnosis like schizophrenia, which people sometimes react to like they've been cursed.

Not everyone experiences a diagnosis so negatively, though, even in psychiatry. For some, a diagnosis is liberating…

Continue reading it here:

Essay pushback

One commenter, after being kind enough to commend my points, remained unconvinced by them:

…[I]n my opinion, labels do more damage than good. When you label a person, that’s all you see – the disease and not the person. Labels work more to satisfy the person doing the labelling, not the person being labelled. Mental health is subjective, but labels allow the professionals to put a bunch of people in one single box because they have certain presentations in common.

This is a common but (I believe) misguided view, but its existence is why I wrote the essay. I think it’s attractive because it sounds admirable: let’s treat people individually, rather than as groups. But it starts to fall apart the minute you think hard about it.

Here’s some of my reply:

Yet, we must name a disease if there is to be any hope of providing good care for the person. Is there a risk that in naming the disease, the person will be seen as nothing more? Certainly. But there’s also the risk, in not naming the disease, that we will be unable to even know what to do about it. Similarly, professionals using labels to group common presentations together is a feature rather than a bug. Imagine if every time a person went to hospital, the doctors had to start from scratch understanding how to help them, without being able to bring their experience to bear? That would be a worse state of things than healthcare pre-modern medicine. So again, the problem isn’t that categorising, it’s if we were so bound to our categories that we missed the differences. Indeed, by allowing us to group similar things, labels in fact help us appreciate differences, wouldn’t you agree?

I want to expand a bit more on that last point: we recognise differences better when we can identify similarities.

Like attracts like—and spotlights uniqueness

Our ability to recognise similarities (which I wrote about here) is the foundation of all our learning—without it, we’d be unable to transfer anything from the experience of others to ours.

In the same way, recognising similar health issues allows professionals to transfer experience from one person to another. It’s the whole foundation, not just of healthcare, but of every human endeavour. And even cooler, when we know for instance that a person has got schizophrenia, or bipolar disorder, it’s easier to focus on the ways they’re unique, or even unusual. Labels help make it easier to set the generalities aside and truly see the individual’s unique personal, socioeconomic or other circumstances

We wouldn’t be able to do that if we weren’t even sure what we were dealing with in the first place. Just ask the people themselves, or their loved ones, who before they know their problems have a name, feel adrift on the waves of their own experience.

And to reiterate: I’m not for one second disputing the fact that labels are misused. It’s just too easy to see the problems of misuse while overlooking bigger problems we can create by dismissing entirely. It’s like people who focus on side effects of measles vaccines when the effects of measles itself—which I have personally seen—are far, far severe (including potentially lethal) and way more likely.

I find that a lot of what I think about are ideas like these: ones that are attractive, but that seem to me misguided. It reminds me again of the quote from Henry Louis Mencken that I shared in my Note before last (Note 71):

Explanations exist; they have existed for all time; there is always a well-known solution to every human problem—neat, plausible, and wrong.

Reality is complex and not as neat as we’d like, and labels help us manage it. We just need to remember that labels aren’t reality, any more than maps are the road itself.

Everyday magic (quote)

Speaking of the complexity of reality, I’ll leave you as I began, with the King himself. Enjoy this quote from his last book I read, about a boy who finds a path into another, magical world. I loved this passage where he reflects on how the people of that world took its magic for granted:

“What about the magic, you ask? The sundial? The night soldiers? The buildings that sometimes seemed to change their shapes? They took it for granted. If you find that strange, imagine a time-traveler from 1910 being transported to 2010 and finding a world where people flew through the sky in giant metal birds and rode in cars capable of going ninety miles an hour. A world where everyone went bopping around with powerful computers in their pockets. Or imagine a guy who’s only seen a few silent black-and-white films plunked down in the front row of an IMAX theater and watching Avatar in 3-D. You get used to the amazing, that’s all. Mermaids and IMAX, giants and cell phones. If it’s in your world, you go with it. It’s wonderful, right?”

—Stephen King, Fairy Tale

If you’ve enjoyed reading this, consider giving this Note a like—that helps others find it, and it makes me happy! Plus, if you have a friend you think would enjoy Notes on Being Human, do share!

What an excellent write up!👍I gained my freedom the moment my ailment was labeled.I think it’s of immense benefit to label the disease other than the individual.