I’ve recently started trying a new approach to my running. It’s based on what’s known as zone 2 training: 80-90% of your cardio workouts being low intensity (running being a prime example) and high-intensity stuff reserved for the remaining 10-20%. It’s apparently been found to improve not just endurance (which makes sense) but also, counterintuitively, speed.

I track my heart rate with my Apple Watch, and last year’s watchOS update happened to come with a heart zone monitoring feature, with alerts when you attain and/or exceed a zone. The aim is to get into and stay within zone 2: 60-70% or so of my maximum heart rate.

The difficulty of deliberate slowness

The surprising thing has been how hard it’s been to slow down and stay slow. I realised quickly that I simply couldn’t run in Zone 2, and needed a different form of exercise. A bit of experimenting at the gym, and I found that I could make it work with stair-stepping machines and with treadmills if I walked at an incline.

That’s when I made the next discovery: although it’s low intensity and didn’t feel effortful, I still found myself sweating far more than when I played badminton, as much as if I were all-out running. I think that was from the steadiness of it: whereas in badminton my heart rate went up more often, it also went down more often when I would stand to serve and such. WIth the zone 2 training, however, there was no stopping and no dropping.

There’s a parable in there, isn’t there? To go faster, we need to slow down, and when we do, it’s surprising how much more difficult that is than simply going all out. It’s like how strength training is so much harder when you really slow down instead of pushing through with the momentum. In those moments, going faster is almost a relief.

Slowing down, it turns out, is a skill, and one that takes time to master.

But in a world where we’re constantly being nudged to hurry, it’s a skill worth learning. In a way, that’s what these Notes are about, isn’t it—I need to slow down to write them, and so do you, to read them.

In that spirit, perhaps consider taking another moment to invite a friend to slow down with you?

A laborious essay

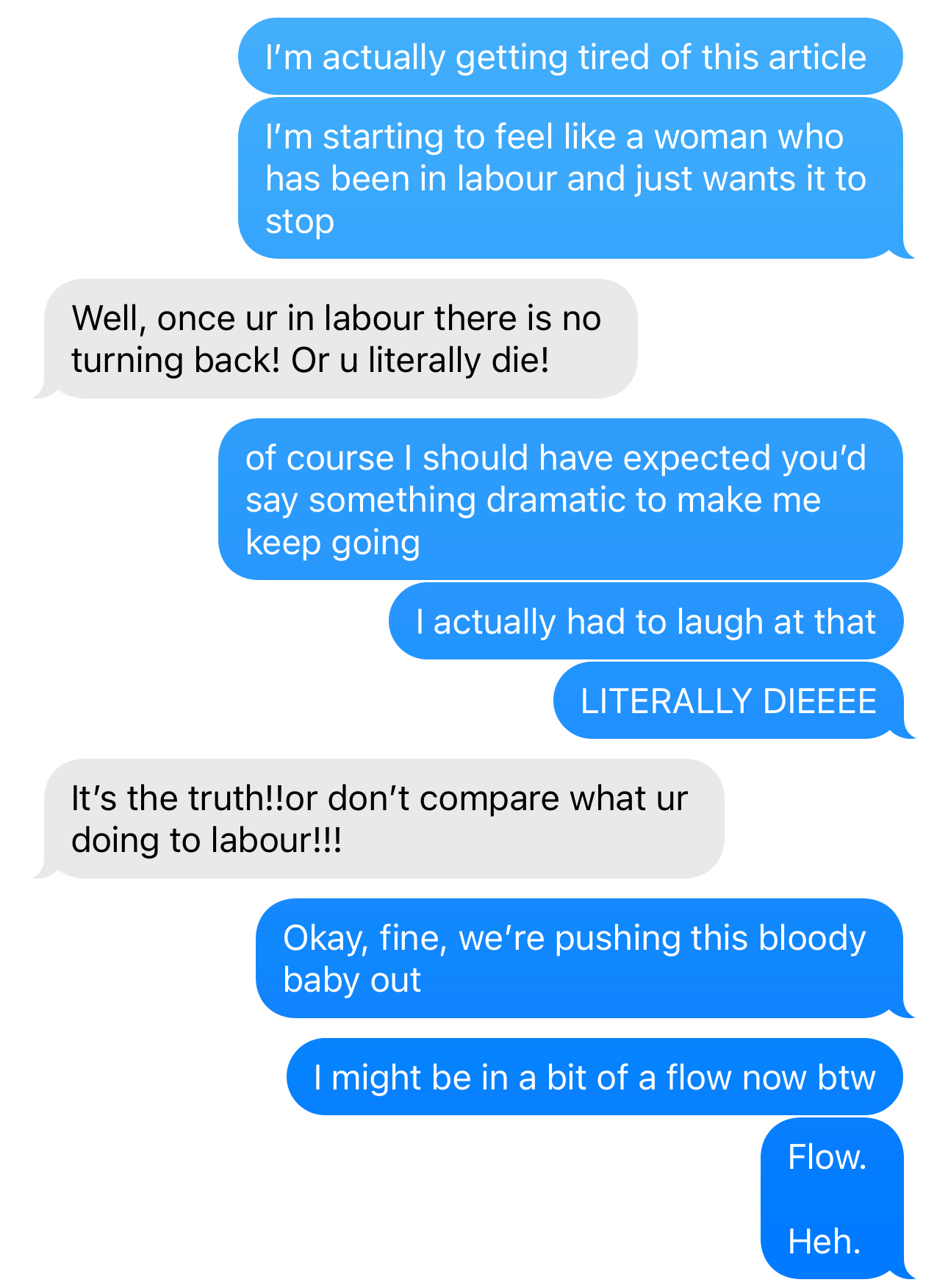

That was my essay this week: the most difficult thing I’ve written in a while, and definitely the hardest this year. I wanted to give up on it several times, and at one point joked with a friend about it feeling like prolonged labour. She was justly quick to admonish me for making the comparison.

I thought a bit about why it was such a difficult essay to write, and I think it’s just because it felt so personal, but also like something people might get upset about. I suppose that’s the intersection of the most difficult stuff to create: something you personally think, but that might anger others. Sometimes, you wait until you’re sure you can say it as respectfully as possible. Other times you just say it because it needs to be said even if you’re the not most suited to say it.

Anyway, I submitted it to a Medium publication and am waiting for feedback. I’ll of course share when it’s published.

The kindness of strangers

This week, I enjoyed a simple but beautiful read from Janna Barrett about getting free coffee from strangers—in New York, of all places! (And whatever you make of that sentence, I promise you the actual story is even better.)

My favourite line:

I practically skipped down the street, with a huge goofy smile that I was both unable and unwilling to wipe off my face. I didn’t care if I looked silly, smiling to no one. I deserved a moment of uncontrollable happiness upon the fruition of a laborious, menial project — and as the recipient of a lengthy act of kindness from about a hundred strangers I’ll never know anything about.

Check out the whole thing.

Enjoyed this? Please share and give this Note a ❤️ to help spread it. And if a friend shared with you, sign up below for new Notes fresh off the press!

If we keep thinking 🤔 about what people’s reaction will be, we won’t say the things we ought to say, but if we think 🤔 of people that will be harmed if we don’t say what we ought to say, then, it’s better to say what we ought to say to help those who really need what we’re saying. We all can’t be right, ‘cos we see things differently and have different views but with cogent points and explanatory notes we can persuade those who don’t understand us and later make a point.It can simply be a constructive speech which will be thrown out as question for people to make suggestion.